A MODERN DISCIPLINE

Corporate affairs – rather than corporate communications or public relations – has only emerged as a dedicated discipline in the past 15 to 20 years. The role is a senior post with some corporate affairs directors, particularly in the FTSE100, leading teams of 100+ staff and managing multi-million pound budgets. Our research show that around 75% report directly to the CEO and the role sits on the executive committee (ExCo) of around 45% of companies in the FTSE100.

Corporate affairs – rather than corporate communications or public relations – has only emerged as a dedicated discipline in the past 15 to 20 years. The role is a senior post with some corporate affairs directors, particularly in the FTSE100, leading teams of 100+ staff and managing multi-million pound budgets. Our research show that around 75% report directly to the CEO and the role sits on the executive committee (ExCo) of around 45% of companies in the FTSE100.

The corporate affairs director is arguably the steward for the organisation’s corporate reputation.

Responsibilities can be extensive and usually include overseeing corporate communications, corporate reputation, media relations, financial PR, public affairs, government relations, internal communications, corporate responsibility, and often, aspects of marketing, digital communications, investor relations and social media. Some corporate affairs practitioners also include customer relations or strategy in their remit.

As the role has evolved, so too have the skills and competencies of post-holders. These individuals are highly regarded internally, with many corporate affairs directors now seen as a critical component of an organisation’s success.

I think good corporate affairs directors, those that run communications, internal, external, media, public affairs etc. have an extremely important functional role within an organisation. The world has changed hugely in the past decade and those that gained their skills in the past 10 years rather than the past 30 years are more professional, thoughtful and rigorous.

FTSE Chairman

The 100+ corporate affairs and communications leaders that participated in this research are senior practitioners and therefore well placed to evaluate career opportunities both within and outside the communications arena.

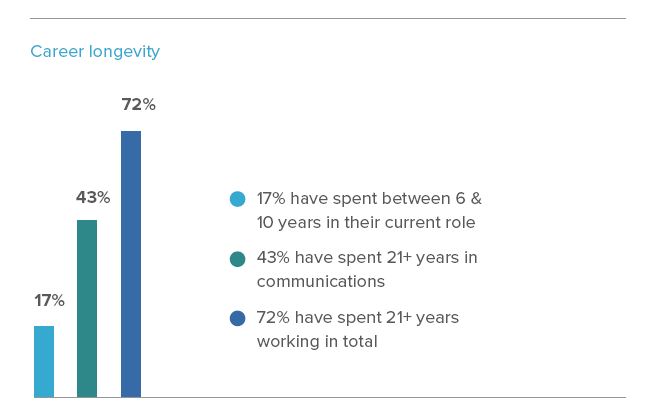

The vast majority (72%) of respondents have spent over 21 years in the work place, with almost half of those (43%) spending that time in communications-specific roles. In terms of their current communications positions, almost 80% have been in situ for less than five years with most of the rest (17%) having been in their current post for between six and 10 years. Just 5% of respondents have been in their current role for more than 11 years.

PROSPECTS AND ASPIRATIONS

However far the role itself has progressed, it was striking to discover how many senior communicators are frustrated about the trajectory of their own careers from here.

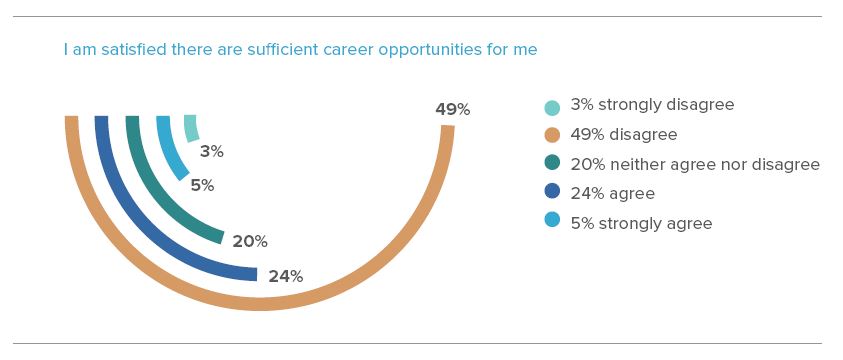

Over half (52%) of corporate communications leaders we surveyed disagreed or strongly disagreed with the suggestion that they had “sufficient opportunities for onward promotion and career development”. This compares with less than one in three who believe there are sufficient opportunities open to them. A fifth of respondents sat on the fence.

The perceived lack of opportunities might explain why the vast majority (over three quarters of respondents) do not see a career for themselves beyond communications in the medium term. Just one in five expect to take on a different, non-communications role in the future.

Those that see opportunities outside of the communications profession envisage taking on the role of a CEO,or marketing or business development roles, among others.

STAYING WITHIN COMMUNICATIONS

The same communications role

The majority of respondents (78%) do not expect to move out of a communications specific role in the next five years. They either want to move but believe there are limited opportunities to expand on their current communications role or to move into a non-communications position. Of course, some are very happy to continue their career within the communications profession.

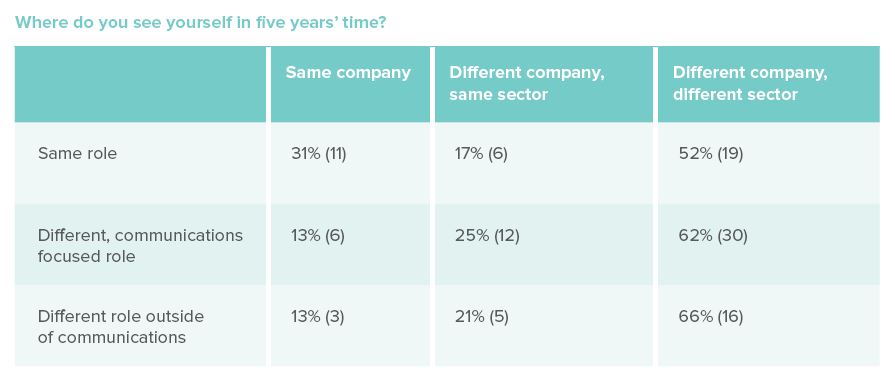

Of those respondents who saw themselves doing the same role, 31% thought they would be doing it for the same company in five years’ time. In other words, they saw no career progression at all. Just over half (52%) thought they would have moved company and sector within five years, while 17% thought that they would be in a different company in the same sector.

What factors determine these respondents’ job mobility? In some cases, corporate affairs directors move for a new challenge or better remuneration. Often, because this is a key role appointed by the CEO, how frequently they move can be determined by changes at the top.

It is a relatively narrow field of expertise, therefore there is an inevitable feeling of a shuffling of the deckchairs on the ship deck.

Communications Leader

Some senior communicators, albeit the minority, are content to remain in their current positions. For them, the increased responsibility and profile of the corporate affairs director position means that they see no need to look outside the brief. Progression means moving to a larger company, perhaps with a bigger global footprint or in a different industry, ideally with increased communications responsibilities.

Some mentioned that communications skills are increasingly transferable between sectors, which allows them to move relatively easily.

Different, communications-focused role

For those expecting to move into another communications-focused position (44% of all respondents), potential next steps include chief marketing officer posts which combine marketing with communications. Other opportunities that respondents planned to explore include senior consultancy positions (either joining or setting up their own communications advisory service for firms or individuals) as well as roles that combine human resources, strategy and communications.

The route from agency life into an inhouse role is well established, but in recent years the launch of advisory boutiques, for example, Milltown Partners, Pagefield and StockWell (now part of Teneo), has seen senior practitioners reverse out again. The trend has gathered pace as corporate reputation has grown in importance. It also appears to be a sensible next step if the opportunities for communicators to progress in a corporate environment are so limited.

For those that choose to remain in-house, the blurring of lines between marketing and communications at some mid-sized corporations was seen by some as a new opportunity. The increasingly central role communications has in successful engagement campaigns versus advertising or marketing alone has got some respondents believing that the corporate affairs role might evolve further into a chief communications officer post, taking overall responsibility for marketing as well as corporate affairs. This, they believe, would provide a dynamic career path that hasn’t really existed until now and reflects the merging of paid-for and earned

communications. Simon Sproule at Aston Martin Lagonda is a good example of an executive combining responsibility for global marketing and global communications.

MOVING OUTSIDE COMMUNICATIONS

Many respondents aired their frustration with how difficult it was to move into other, broader management roles or into alternative lines of business. They are not alone. There are very few examples of communications leaders having made a move outside of the communications profession and consequently there are very few role models to emulate.

Of the three options offered in the survey, a far greater proportion (66%) of those that envisaged a non-communications role in five years’ time said they would move to a different company in a different sector to achieve it. Almost 90% said they would move company.

Only 13% of these respondents thought they could move beyond communications with their existing employer. This offers food for thought for chairmen and CEOs who are intent on encouraging in-house talent. However, the finding is at odds with our own evidence (collected in Section 7 ) which shows that half of former corporate affairs directors who have

gone on to other non-communications roles achieved this only after being promoted into a broader role internally.

NED roles

NED roles are, by quite some margin, the preferred career path for communications leaders to step outside their profession. Obviously NED roles are part-time and therefore can be held in addition to respondents’ current positions rather than directly replacing them – but they do offer a glimpse of a “plural” future and can serve to extend a corporate career long after full-time posts are exhausted.

My best shot so far has been to take up a series of trustee roles over recent years for some great causes. But I recognise that this is not the same thing. I am simply not approached about NED roles but would dearly love to be as long as they were paid for. I would have thought there should be ample opportunity within a broad spectrum of companies for people with our skill set and more.

Communications Leader

Other leadership roles

Outside of communications and NED roles, respondents saw their future in either a CEO position (such as in a not-for-profit organisation), business development, operations or other leadership roles in another part of the business or in a different organisation. Executive coaching was also mentioned as an option. Whilst CEO positions are difficult to secure, a small number of former corporate affairs directors have been successful in securing CEO positions for trade associations. This makes sense, as trade associations require excellent communications and advocacy skills, combined with an understanding of policy areas and the ability to engage with multiple stakeholders – often the very skills that corporate affairs directors possess. But what is a step up in profile is inevitably a step down in remuneration, even if it opens up more opportunities ahead.

Those corporate affairs directors that currently sit on the executive committee felt slightly more positive about their long-term career prospects than their peers that don’t have a seat at the table. These ExCo members cited potential moves into operational, strategic or marketing roles but pointed out that this is a long-term plan and may likely involve a career side-step in order to gain the necessary experience.

SKILLS AND COMPETENCIES

We asked communications leaders to review the skills and competencies particular to their role and rank them by their importance in enhancing their career prospects – with particular reference to making them suitable candidates for NED roles. A number of respondents pointed out that it is the breadth of their skills, rather than any specific competency, that makes them suitable for NED and other business leadership roles. Setting that point aside, their skills were ranked, with 1 being the most important, as follows:

Communications leaders’ ability to manage corporate reputation and identify reputation risk was deemed as the most important competency (1 and 2), closely followed by their capacity to bring a perspective from outside the business (3). Their talent in providing counsel to the executive team – as well as being a sounding board for public opinion – was also considered important (4).

Slightly lower down the list was experience of building relationships across multiple stakeholders (5) such as the media, government, employees, influencers, NGOs, shareholders, local communities etc.; their extensive knowledge of how to manage corporate crises and issues (6), as well as their proficiency in defending the brand (7). Communications leaders ranked their capacity to act as the company’s conscience by helping executives not only to say the right thing but do the right thing (8).

Overall, the majority of corporate affairs directors we spoke to believe that it is the multi-faceted makeup of the communications role, with its breadth of hard skills coupled with softer influencing and engagement capability, that mark them out as credible contenders for NED and other senior leadership roles.

GETTING CAREERS ADVICE

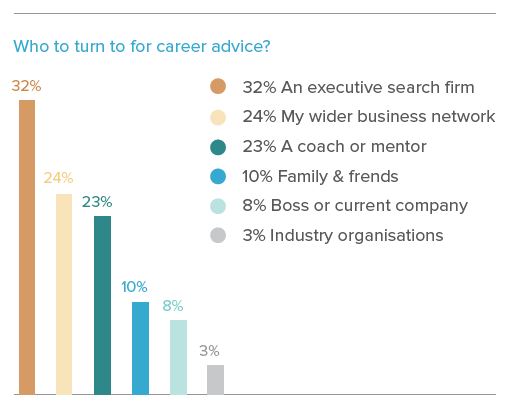

Given the challenges facing communications directors in developing their careers, we wanted to know who they turned to for advice and support.

Reinforcing the belief that most communications directors need to change jobs to progress, headhunters came top by some way. Some 32% of respondents said they would turn to an executive search firm first for careers advice.

Using their own business network came second at 24%, closely followed by a coach or mentor at 23%. Just 10% would first turn to their family and friends, and only 8% would go to their current boss. Only 3% of respondents would turn to industry organisations, such as the CIPR and PRCA for career guidance. This spells bad news for these bodies that claim to help members navigate their profession.